Round-Trip Privacy with NFSv4

Avishay Traeger, Kumar Thangavelu, and Erez Zadok

Stony Brook University

1

Abstract

With the advent of NFS version 4, NFS security is more important than

ever. This is because a main goal of the NFSv4 protocol is

suitability for use on the Internet, whereas previous versions were

used mainly on private networks. To address these security concerns,

the NFSv4 protocol utilizes the RPCSEC_GSS protocol and allows

clients and servers to negotiate security at mount-time. However,

this provides privacy only while data is traveling over the wire.

We believe that file servers accessible over the Internet should

contain only encrypted data. We present a round-trip privacy scheme

for NFSv4, where clients encrypt file data for write requests, and

decrypt the data for read requests. The data stored by the server on

behalf of the clients is encrypted. This helps ensure privacy if the

server or storage is stolen or compromised. As the NFSv4 protocol was

designed with extensibility, it is the ideal place to add round-trip

privacy. In addition to providing a higher level of security than

only over-the-wire encryption, our technique is more efficient, as the

server is relieved from performing encryption and decryption.

We developed a prototype of our round-trip privacy scheme. In our

performance evaluation, we saw throughput increases of up to 24%, as

well as good scalability.

1 Introduction

The first two stated goals of NFS version 4 are "improved access and

good performance on the Internet" and "strong security with

negotiation built into the protocol" [19]. Whereas

previous versions of NFS were designed for private networks, NFSv4 was

designed to be used over the Internet. NFS systems will clearly be

harder to secure in this environment, as reflected by the NFSv4 goal

of having strong built-in security.

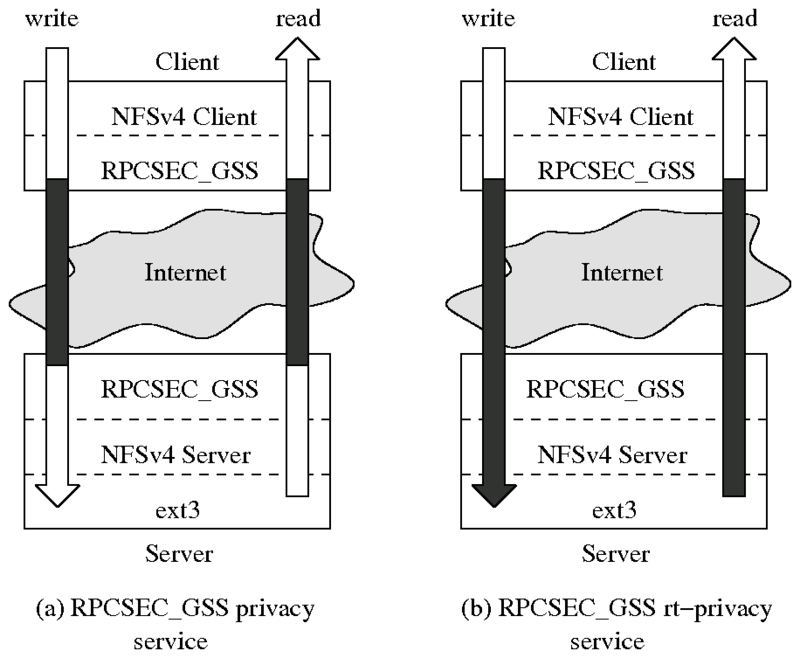

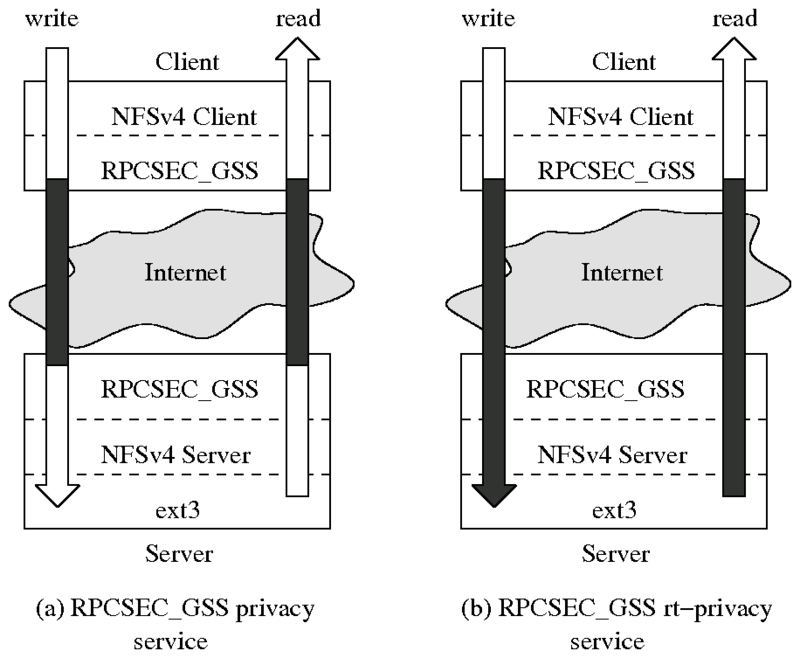

Figure 1: A comparison of the current

RPCSEC_GSS privacy service and our round-trip privacy (rt-privacy)

service. The arrows depict data transfers, where the white portions

represent clear-text file data and the black portions represent

cipher-text.

The NFSv4 protocol provides this strong security by utilizing the

RPCSEC_GSS protocol [6]. RPCSEC_GSS provides

authentication, integrity, and privacy. Although RPCSEC_GSS secures

communications between clients and servers, file data resides as

clear-text in the server's caches and storage. This leaves data

vulnerable, especially for NFSv4 servers that are open to connections

from the Internet. Additionally, if servers see only cipher-text,

companies could offer storage outsourcing services using NFSv4. These

services are attractive as they reduce data management costs for

users.

The standard RPCSEC_GSS privacy service provides

authentication, integrity, and privacy on the wire.

We developed our round-trip privacy scheme as a new RPCSEC_GSS

service called rt-privacy. With rt-privacy, clients

encrypt file data on write operations, and decrypt it on

read operations. Other parts of the RPC are encrypted over

the wire as they are in the privacy service. Additionally

the rt-privacy service provides the same authentication and

integrity on the wire as privacy. In our scheme, clear-text

file data resides only on authenticated clients. This is depicted in

Figure 1.

NFSv4 was designed with extensibility in mind. This allowed us to

integrate stronger privacy without modifying the protocol. Because

NFSv4 utilizes RPCSEC_GSS, which is also an extensible protocol, we

were able to cleanly introduce a new privacy service that is

negotiated at mount-time.

Additionally, the extensibility of RPCSEC_GSS meant that we could

leverage a secure and established protocol, rather than create a new

one.

A trade-off often exists between security and performance. The

rt-privacy service not only provides better privacy, but also

relieves the server from performing encryption and decryption on file

data. This is an important savings, as the server is generally the

bottleneck in client-server environments. Our performance evaluation

shows that although rt-privacy has degraded throughput when

performing sequential reads with read-ahead, all other workloads

tested show an improvement-as much as 24%. Additionally, we

benchmarked rt-privacy with as many as 96 processes, and saw

that it scales well.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. We discuss related

work in Section 4. We describe the design and

implementation of our new privacy service in Section 2,

and evaluate its performance in Section 3. We conclude

in Section 5.

Figure 1: A comparison of the current

RPCSEC_GSS privacy service and our round-trip privacy (rt-privacy)

service. The arrows depict data transfers, where the white portions

represent clear-text file data and the black portions represent

cipher-text.

The NFSv4 protocol provides this strong security by utilizing the

RPCSEC_GSS protocol [6]. RPCSEC_GSS provides

authentication, integrity, and privacy. Although RPCSEC_GSS secures

communications between clients and servers, file data resides as

clear-text in the server's caches and storage. This leaves data

vulnerable, especially for NFSv4 servers that are open to connections

from the Internet. Additionally, if servers see only cipher-text,

companies could offer storage outsourcing services using NFSv4. These

services are attractive as they reduce data management costs for

users.

The standard RPCSEC_GSS privacy service provides

authentication, integrity, and privacy on the wire.

We developed our round-trip privacy scheme as a new RPCSEC_GSS

service called rt-privacy. With rt-privacy, clients

encrypt file data on write operations, and decrypt it on

read operations. Other parts of the RPC are encrypted over

the wire as they are in the privacy service. Additionally

the rt-privacy service provides the same authentication and

integrity on the wire as privacy. In our scheme, clear-text

file data resides only on authenticated clients. This is depicted in

Figure 1.

NFSv4 was designed with extensibility in mind. This allowed us to

integrate stronger privacy without modifying the protocol. Because

NFSv4 utilizes RPCSEC_GSS, which is also an extensible protocol, we

were able to cleanly introduce a new privacy service that is

negotiated at mount-time.

Additionally, the extensibility of RPCSEC_GSS meant that we could

leverage a secure and established protocol, rather than create a new

one.

A trade-off often exists between security and performance. The

rt-privacy service not only provides better privacy, but also

relieves the server from performing encryption and decryption on file

data. This is an important savings, as the server is generally the

bottleneck in client-server environments. Our performance evaluation

shows that although rt-privacy has degraded throughput when

performing sequential reads with read-ahead, all other workloads

tested show an improvement-as much as 24%. Additionally, we

benchmarked rt-privacy with as many as 96 processes, and saw

that it scales well.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. We discuss related

work in Section 4. We describe the design and

implementation of our new privacy service in Section 2,

and evaluate its performance in Section 3. We conclude

in Section 5.

2 Design and Implementation

We designed our round-trip privacy scheme with two main goals in mind:

- Privacy: only authenticated clients should have access

to clear-text data.

- Efficiency: the server should be freed from encrypting

and decrypting data.

We present our threat model in Section 2.1. We

discuss the design of our round-trip privacy service in

Section 2.2. We describe the methods that we used for

encrypting and decrypting file data in Section 2.3,

and our key-management scheme in Section 2.4.

2.1 Threat Model

We assume that only authenticated clients are trusted, and that the

network, unauthenticated clients, as well as the NFSv4 server are

untrusted. Our goal is to ensure privacy while data is being

transmitted over the network and while it resides on the server (both

in memory and on persistent storage). We do not currently prevent

attackers from maliciously modifying or deleting data. However, we

plan to provide round-trip integrity in the future to detect file

modifications.

2.2 Round-Trip Privacy

There are several possible ways to design round-trip privacy for

NFSv4. We discuss three alternatives before describing ours to

illustrate the benefits of our choice. One possibility is to encrypt

all wire traffic (using RPCSEC_GSS or SSH, for example) and

separately encrypt data being written to the server's disks. This

scheme has three drawbacks. First, data is present unencrypted in the

server's memory, allowing an attacker to potentially view it. Second,

keys are managed on the server, which is untrusted. Third, the same

data is encrypted and decrypted multiple times in a single operation.

In a write request, for example, the client encrypts the

data, the server decrypts the data, and then re-encrypts it before

saving it to disk. Similar behavior is seen in read

requests. This is especially bad since the server, which is usually

the performance bottleneck in a network file system, is doing

unnecessary work.

Another possibility would be to encrypt the file data at the client,

above the NFS layer, perhaps by using a stackable file system such as

NCryptfs [21] or eCryptfs [9].

Stackable file systems are a useful technique for adding functionality

to existing file systems [23]. Stackable file systems

overlay another lower file system (the NFSv4 client in this

case), and intercept file system events and data bound from user

processes to the lower file system. In the case of encryption

stackable file systems, file data is encrypted on write

operations before passing it to the lower file system, and is

decrypted on read operations after it is received from the

lower file system.

However, this scheme does not provide authentication and integrity,

and provides privacy only for file data (not for NFS commands and

arguments). If one were to use RPCSEC_GSS to provide this, then

clients would be encrypting file data twice for write

requests, and servers would be decrypting once. Servers encrypt file

data once, and clients decrypt twice for read requests. This

puts less load on the server than the previous scheme, but unnecessary

work is still being performed.

One additional method for implementing round-trip privacy would be to

add a new RPCSEC_GSS privacy service type that would not encrypt or

decrypt file data. A user could then mount an encryption stackable

file system on top of the NFS client to handle the encryption and

decryption of file data. The benefit of using this design is that it

relies on stackable file systems that are already in use, and does not

perform unnecessary encryption or decryption operations. One downside

is that it would be difficult to coordinate the privacy settings

between the stackable file system and the RPC layer. The system would

need to be carefully configured to ensure that anything not being

encrypted at the RPC layer was being encrypted by the stackable file

system. Additionally, it would be difficult to implement a feature

where the user could selectively encrypt files on storage because

information about which files are encrypted would need to traverse

several programming layers. Another concern with this design is that

performance may suffer because of adding an additional file system

layer, and is exacerbated by the fact that the stackable file system

performs its own caching. Since both the stackable file system and

the NFS client will have their own caches, the cache size is

effectively halved, which can impact performance.

We chose to implement our round-trip privacy scheme by adding a new

service type to RPCSEC_GSS. The NFSv4 protocol utilizes the

RPCSEC_GSS protocol [6] to provide authentication,

integrity, and privacy. RPCSEC_GSS uses the GSS-API (Generic

Security Service API), and consists of security context creation, RPC

data exchange, and security context destruction. During security

context creation, a client may specify the security mechanism, the

Quality of Protection (cryptographic algorithm to be used), and the

type of service. The current security mechanisms implemented by Linux

are Kerberos and SPKM-3. The type of service is one of

privacy, integrity, or none. All types of

service perform authentication, and privacy includes

integrity as well. Once a context is set up successfully, the RPC

data exchange phase may begin. When the client has finished the data

exchange, it informs the server that it no longer requires the

security context, and the context is then destroyed.

We have added a new service type called rt-privacy

(round-trip privacy) to the existing RPCSEC_GSS service types. For

operations other than read and write,

rt-privacy is identical to privacy, providing

authentication, integrity, and privacy over the wire. For

write operations, the file data is encrypted using strong

encryption since it will be stored persistently, whereas the remainder

of the RPC (such as NFS commands and arguments) is encrypted as in

privacy. The file data encryption is discussed further in

Section 2.3. The server decrypts everything but the

file data; this allows the server to access the meta-data that it

needs to process the RPC, but leaves the data to be written to storage

encrypted. For read operations, the server does not encrypt

the file data, but does encrypt the remainder of the RPC. Using the

rt-privacy service, the server performs no file data

encryption or decryption, reducing its load, while providing

round-trip privacy.

In addition to avoiding unnecessary encryption and decryption, we

chose to implement our scheme as an RPCSEC_GSS service because: (1)

it allows us to encrypt all NFS-related traffic (this cannot be done

at the file system level, for example), (2) it allows us to easily

distinguish file data from the rest of an RPC so that it can be

handled separately (this is more difficult at the transport level, for

example), (3) it allows us to implement round-trip privacy by adding a

service to RPCSEC_GSS, which is well-known and tested security

protocol, and (4) the extensibility of RPCSEC_GSS allowed us to

cleanly add this new service and have it be negotiated at mount time.

We have implemented our RPCSEC_GSS service type only for the Kerberos

security mechanism, but adding it to the SPKM-3 mechanism would not be

difficult. In addition to our changes to RPCSEC_GSS, we modified the

NFSv4 implementation to support our key management (see

Section 2.4). Because NFSv2 and NFSv3 can also use

RPCSEC_GSS, porting the key management code would allow them to use

rt-privacy as well. In total, we added 1,840 lines of

code, and deleted 21 lines. The total development time was two

part-time graduate student working for three months.

2.3 File Data Encryption

By default, we encrypt file data with AES using a 128-bit key, which

is the default for other current file data encryption

systems [9] (privacy currently uses DES-64).

This should be sufficiently strong for encrypting most persistent

data. If stronger privacy guarantees are needed however, it is

trivial to use another supported encryption algorithm or to change the

key size because we utilize the Linux kernel's flexible CryptoAPI.

The Linux implementation of NFSv4 performs write operations at offsets

that are not necessarily block-aligned nor multiples of the block

size, which complicates the use of a block cipher. One possible

solution to this issue is to modify NFS's write behavior to write

whole, aligned blocks. However, writing a partial block when the

remainder of the block is not cached would hurt performance because

the client would have to read a full page from the server, decrypt it,

complete the block using the new data, and then encrypt and write back

the full block. Instead, we use counter-mode (CTR-mode)

encryption [5]. This turns the block

cipher into a stream cipher, which allows for variable-sized writes

and random access during decryption. CTR mode obviates the need to be

concerned with cipher block sizes and padding. We use the encryption

block number for the counter. It has been proven that CTR-mode

encryption is as secure as CBC-mode encryption [13].

2.4 Key Management

We have implemented a simple key-management system that can be cleanly

extended to provide more advanced functionality, such as per-user and

per-group keys. After mounting the NFSv4 file system, the

administrator enters a password on the client using the ioctl

system call. The main encryption key is generated from the password

using the PKCS #5 specification [18]. Neither the

password nor the main encryption key are persistently stored. Keys

are randomly generated for each file, which are encrypted and

decrypted using the main encryption key. Per-file keys are stored in

the file's extended attribute on the server. This requires that the

exported file system support extended attributes, but most popular

Linux file systems support this feature. Per-file keys and are cached

in the file's in-memory inode (a per-file data structure) on the

client. Caching the key allows us to reduce the number of key

exchanges significantly. Although this key-management system is

currently not flexible enough for real-world use, it is sufficient for

our prototype, and can easily be extended to provide added

functionality.

A feature that was introduced in NFSv4 is the compound

procedure, which allows clients to send several operations in one

"compound," reducing the number of RPCs that are transmitted. We

utilize compounds to store and retrieve the per-file keys. The key is

stored on the first write operation to a file, and is

retrieved on read and write operations when the key

is not in the client's cache.

The NFSv4 protocol supports named attributes, which are

similar to extended attributes. This allows systems to use attributes

that are not explicitly supported by the protocol without modifying

it. We would have utilized this extensibility feature to transmit the

per-file keys, but it is not yet available in the Linux NFSv4

implementation. To overcome this problem, we extended the NFSv4

protocol to add a new recommended attribute; these attributes

are hard-coded, unlike the named attributes. This was the

only change made to the NFSv4 protocol, and is temporary.

3 Evaluation

The main questions that we wanted to answer when evaluating the

performance of our round-trip privacy scheme were:

- With rt-privacy, the server is relieved from performing

encryption and decryption, but the file data encryption performed on

the client is more costly. How will this affect workloads where the

server is not heavily loaded?

- How well does rt-privacy scale?

We evaluated our round-trip privacy service using up to seven

identical machines; one server and up to six clients.

Each was a Dell 1800 with a 2.8GHz Intel Xeon processor, 2MB L2

cache, and 1GB of RAM. The machines were equipped with 250GB Maxtor

7L250S0 SCSI disks. Each machine used one disk as its system disk,

and the server used an additional disk for the benchmark data. All

machines were connected with gigabit Ethernet by a dedicated HP

ProCurve 3400cl switch. The machines ran Fedora Core 6 updated as of

May 10, 2007, kernel version 2.6.22-rc3.

All local file systems used ext3 with extended attributes enabled. A

list of installed package versions, the kernel configuration, and the

micro-benchmark source code are available at

www.fsl.cs.sunysb.edu/project-secnetfs.html.

We used the Autopilot v.2.0 [20] benchmarking

suite to automate the benchmarking procedure. We configured Autopilot

to run all tests at least ten times, and compute 95% confidence

intervals for the mean elapsed, system, and user times using the

Student-t distribution. In each case, the half-width of the

interval was less than 5% of the mean. We report the mean of each

set of runs. Throughput is calculated as the amount of data

transferred, divided by the longest elapsed time of all client

processes.

As we had only six client machines available to us, configurations

involving more than 6 processes used more than one process per machine

(evenly distributed among the clients).

To minimize the influence of consecutive runs on each other, all file

systems, including the exported file system, were re-mounted between

runs. In addition, the exported file system was recreated. The page,

inode, and dentry caches were cleaned between runs on all machines

using the Linux kernel's drop_caches mechanism.

3.1 Write Throughput

To measure write throughput, we used sequential and random write

workloads generated by a workload generator that we created. Each

process created a 1GB file on the server by writing 1,024 1MB chunks.

Each file was created in its own directory, and sync was

called at the conclusion of the benchmark.

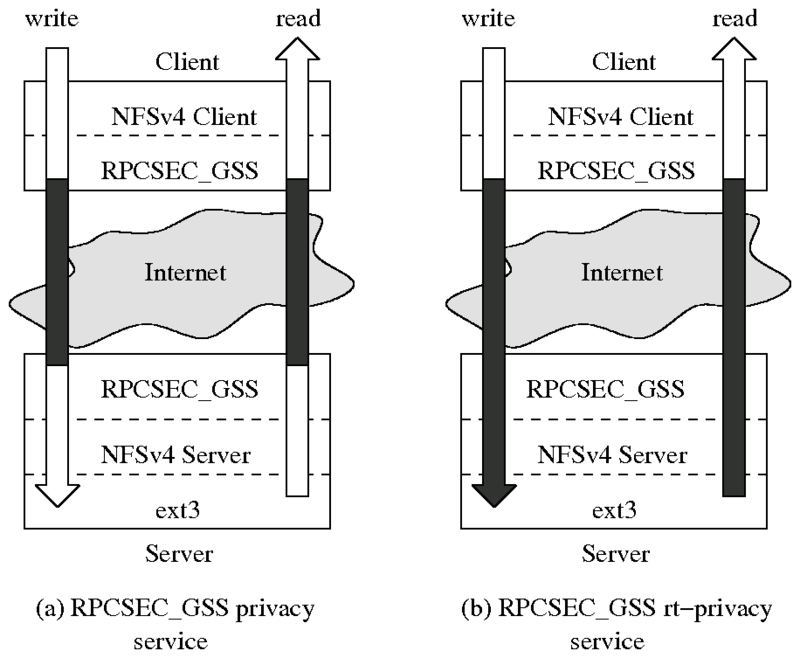

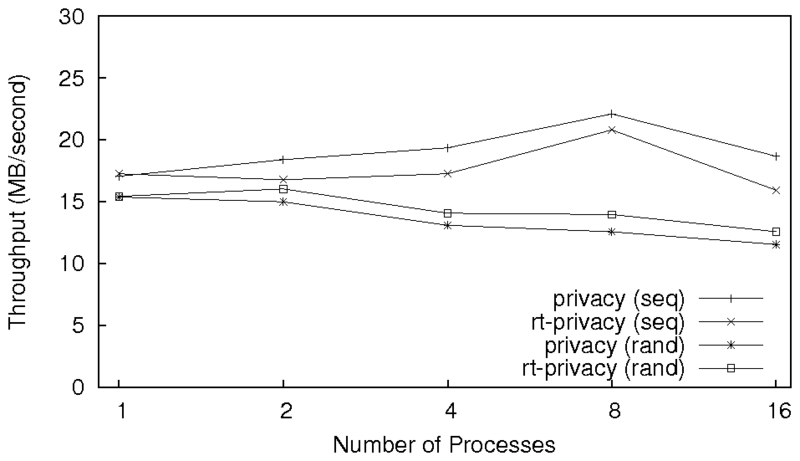

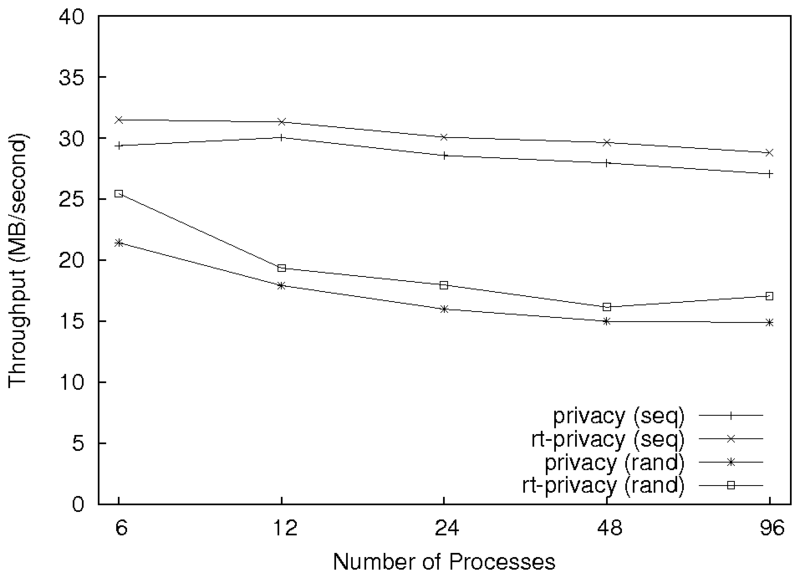

Figure 2: Results for the sequential and random write workloads

running on one client machine with a varying number of processes.

Note: the x-axis is logarithmic.

The results for one client machine are summarized in

Figure 2. As we can see,

rt-privacy consistently performs better than

privacy. To better explain the performance improvement, we

profiled the client's encryption function and the server's decryption

function using OSprof [12]. The profiles showed that

for the one-process sequential workload, the client's encryption

function for rt-privacy is 1.3 times slower because of the

stronger encryption. However, while encryption on the client is

marginally slower with rt-privacy, decryption on the server

is 7.1 times faster because file data does not need to be processed.

Combined, the total encryption and decryption time for a write request

and reply is 1.9 times faster with rt-privacy.

For sequential writes, the throughput for rt-privacy is

approximately 32.0 MB/sec, and the throughput for privacy is

approximately 24.4 MB/sec (approximately a 24% improvement). The

results do not improve with added processes because of coarse-grained

locking in the client code. This was confirmed with OSprof. If we

run the experiment with two client machines, with one process on each

machine, rather than one client machine with two processes, the

throughput for rt-privacy increases to 40.8 MB/sec and the

throughput for privacy increases to 31.6 MB/sec. This is

because we remove the lock contention from the client by running the

processes on two separate machines.

Random write behavior differs from sequential write in two main ways.

First, the NFS client cannot coalesce as many sequential write

requests when requests are to random locations in the file. However,

the NFSv4 client used the default write size of 128KB, and the

application was writing 1MB chunks. To the NFSv4 client, each chunk

was seen as eight sequential writes, so coalescing requests did not

differ between the workloads. The second way in which the behaviors

differ is longer disk seeks on the server for random writes. For both

privacy and rt-privacy, the random write results

with one process are statistically indistinguishable from the

corresponding sequential write results. However, when the number of

processes is increased, the random write performance decreases. This

is because each process writes 1GB of data, and the server machine has

1GB of RAM. As more data is written on the server, and is written

more quickly due to the added number of clients, the server must flush

file data to disk more often. Additionally, if the number of dirty

pages passes a specified threshold, these writes are performed

synchronously. This can be seen in the sharp drop in throughput for

sixteen processes in Figure 2, .

Figure 2: Results for the sequential and random write workloads

running on one client machine with a varying number of processes.

Note: the x-axis is logarithmic.

The results for one client machine are summarized in

Figure 2. As we can see,

rt-privacy consistently performs better than

privacy. To better explain the performance improvement, we

profiled the client's encryption function and the server's decryption

function using OSprof [12]. The profiles showed that

for the one-process sequential workload, the client's encryption

function for rt-privacy is 1.3 times slower because of the

stronger encryption. However, while encryption on the client is

marginally slower with rt-privacy, decryption on the server

is 7.1 times faster because file data does not need to be processed.

Combined, the total encryption and decryption time for a write request

and reply is 1.9 times faster with rt-privacy.

For sequential writes, the throughput for rt-privacy is

approximately 32.0 MB/sec, and the throughput for privacy is

approximately 24.4 MB/sec (approximately a 24% improvement). The

results do not improve with added processes because of coarse-grained

locking in the client code. This was confirmed with OSprof. If we

run the experiment with two client machines, with one process on each

machine, rather than one client machine with two processes, the

throughput for rt-privacy increases to 40.8 MB/sec and the

throughput for privacy increases to 31.6 MB/sec. This is

because we remove the lock contention from the client by running the

processes on two separate machines.

Random write behavior differs from sequential write in two main ways.

First, the NFS client cannot coalesce as many sequential write

requests when requests are to random locations in the file. However,

the NFSv4 client used the default write size of 128KB, and the

application was writing 1MB chunks. To the NFSv4 client, each chunk

was seen as eight sequential writes, so coalescing requests did not

differ between the workloads. The second way in which the behaviors

differ is longer disk seeks on the server for random writes. For both

privacy and rt-privacy, the random write results

with one process are statistically indistinguishable from the

corresponding sequential write results. However, when the number of

processes is increased, the random write performance decreases. This

is because each process writes 1GB of data, and the server machine has

1GB of RAM. As more data is written on the server, and is written

more quickly due to the added number of clients, the server must flush

file data to disk more often. Additionally, if the number of dirty

pages passes a specified threshold, these writes are performed

synchronously. This can be seen in the sharp drop in throughput for

sixteen processes in Figure 2, .

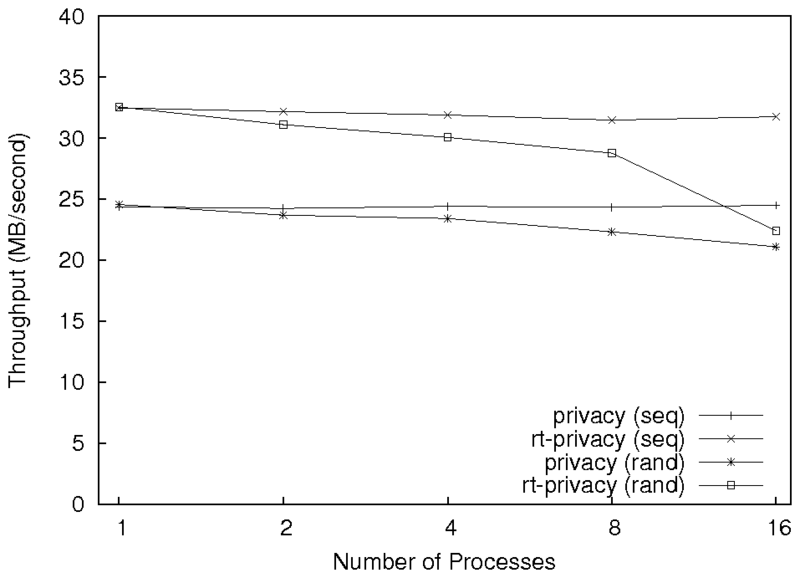

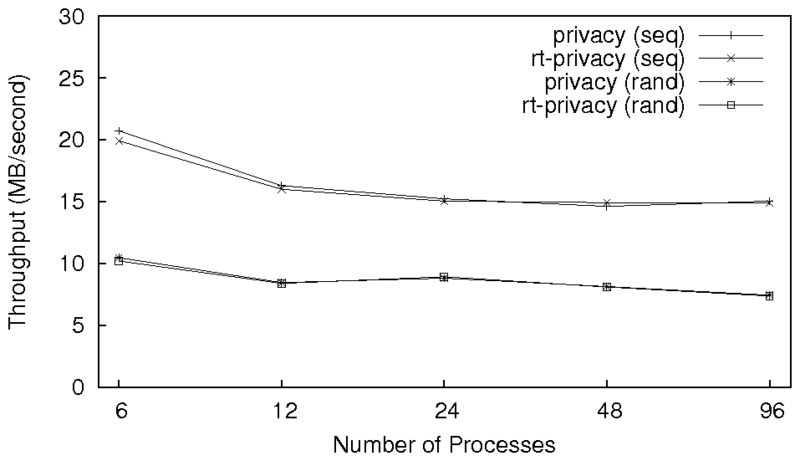

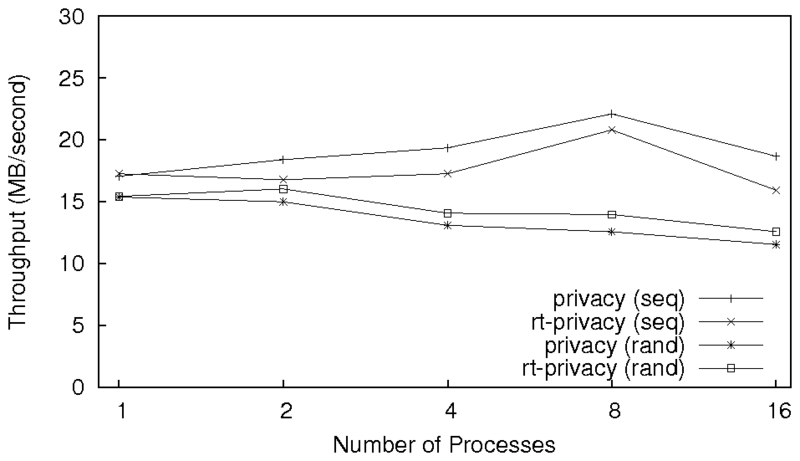

Figure 3: Results for the sequential and random write workloads

running on six client machines with a varying number of processes on

each. Note: the x-axis is logarithmic.

To see how well the rt-privacy service scales, we ran the

write workloads using six client machines, with multiple processes on

each (up to 96 processes in total). The results are shown in

Figure 3. As we can see, the

rt-privacy service has a similar degradation in throughput as

privacy, but maintains a higher throughput.

The decrease in throughput as more processes are added is due to the

server being more loaded, and requests therefore take longer to

process on average.

Figure 3: Results for the sequential and random write workloads

running on six client machines with a varying number of processes on

each. Note: the x-axis is logarithmic.

To see how well the rt-privacy service scales, we ran the

write workloads using six client machines, with multiple processes on

each (up to 96 processes in total). The results are shown in

Figure 3. As we can see, the

rt-privacy service has a similar degradation in throughput as

privacy, but maintains a higher throughput.

The decrease in throughput as more processes are added is due to the

server being more loaded, and requests therefore take longer to

process on average.

3.2 Read Throughput

To measure read throughput, we ran both sequential and random read

workloads

using the same configuration as the write benchmarks. Before starting

the benchmarks, we created a 1GB file on the server in its own

directory for each client process. We cleaned the caches before each

run.

As with the write micro-benchmark, we used OSprof to examine the

encryption and decryption overheads when running a sequential workload

with one process. In this case we were interested in the encryption

method on the server and the decryption method on the client.

We found that for rt-privacy, the client-side decryption

function was 1.2 times slower than privacy, but its

server-side encryption function was 7.4 times faster because it does

not encrypt file data. Combined, the rt-privacy functions

were 1.5 times faster.

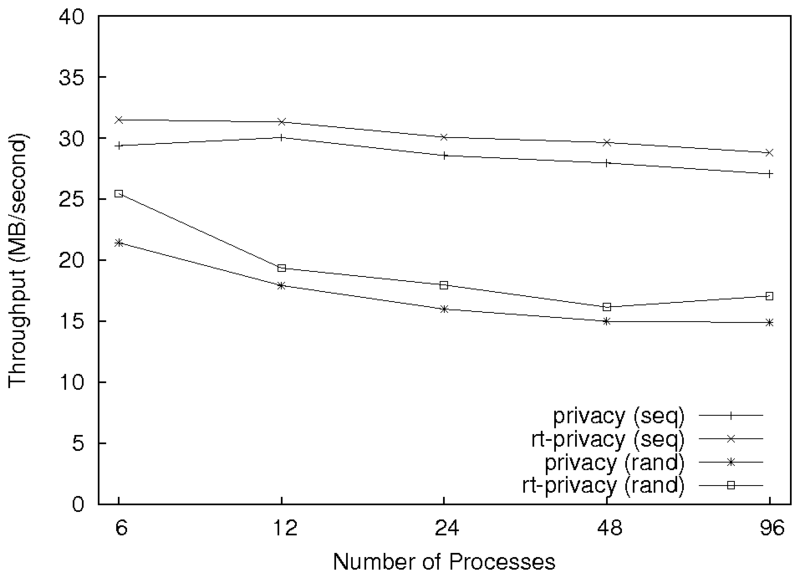

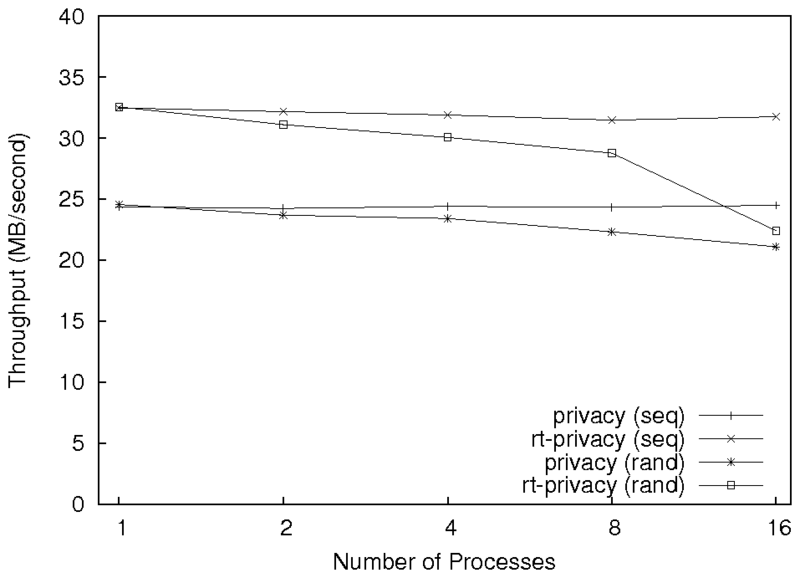

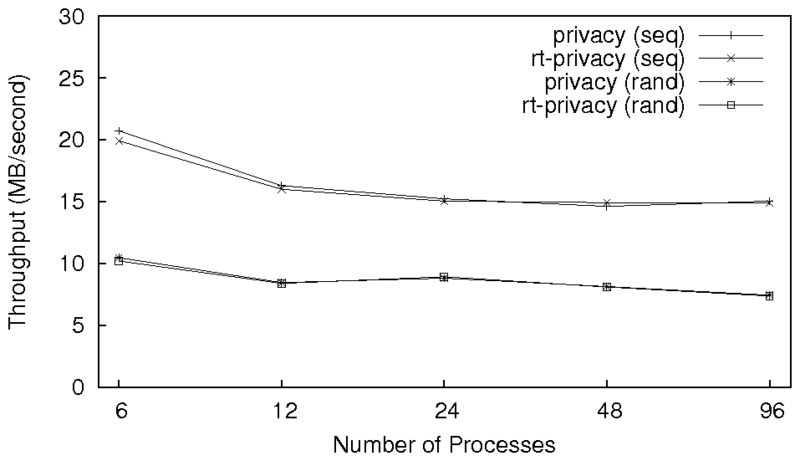

Figure 4: Results for the sequential and random read workloads

running on one client machine with a varying number of processes.

Note: the x-axis is logarithmic.

Figure 4 shows the results for several

processes running the read workloads on one client machine. For

sequential reads with one process, the results are statistically

indistinguishable. As more are added, we see that rt-privacy

does not perform as well as privacy (the throughput for

rt-privacy is as much as 14.7% lower). This was surprising,

as the profiles indicate that rt-privacy should be faster.

We discovered that rt-privacy had lower throughput due to the

NFS client performing read-ahead. Although the server-side encryption

function performed better for rt-privacy, much of this was

performed off-line because of read-ahead. The client-side encryption,

however, has a greater effect on the elapsed time.

By default, the Linux NFSv4 client is configured to perform at most

fifteen read-ahead RPCs. In the source code, the authors state that

users working over a slow network may want to reduce the amount of

read-ahead for improved interactive response. This may be a common

scenario with NFSv4 since it was designed to be used over the

Internet. By reducing the maximum number of read-ahead RPCs to 1, we

saw that the throughput for rt-privacy was between 4.2% and

23.0% higher than privacy. It should be noted that even in

situations where throughput suffered, the server performed

significantly less work when using rt-privacy, alleviating

load from the server machine that is generally the bottleneck. When

running the random read workload, the throughput for

rt-privacy is as much as 10.4% higher than that of

privacy. This is because the Linux kernel reduces read-ahead

when it sees that read-ahead is not effective.

Figure 4: Results for the sequential and random read workloads

running on one client machine with a varying number of processes.

Note: the x-axis is logarithmic.

Figure 4 shows the results for several

processes running the read workloads on one client machine. For

sequential reads with one process, the results are statistically

indistinguishable. As more are added, we see that rt-privacy

does not perform as well as privacy (the throughput for

rt-privacy is as much as 14.7% lower). This was surprising,

as the profiles indicate that rt-privacy should be faster.

We discovered that rt-privacy had lower throughput due to the

NFS client performing read-ahead. Although the server-side encryption

function performed better for rt-privacy, much of this was

performed off-line because of read-ahead. The client-side encryption,

however, has a greater effect on the elapsed time.

By default, the Linux NFSv4 client is configured to perform at most

fifteen read-ahead RPCs. In the source code, the authors state that

users working over a slow network may want to reduce the amount of

read-ahead for improved interactive response. This may be a common

scenario with NFSv4 since it was designed to be used over the

Internet. By reducing the maximum number of read-ahead RPCs to 1, we

saw that the throughput for rt-privacy was between 4.2% and

23.0% higher than privacy. It should be noted that even in

situations where throughput suffered, the server performed

significantly less work when using rt-privacy, alleviating

load from the server machine that is generally the bottleneck. When

running the random read workload, the throughput for

rt-privacy is as much as 10.4% higher than that of

privacy. This is because the Linux kernel reduces read-ahead

when it sees that read-ahead is not effective.

Figure 5: Results for the sequential and random read workloads

running on six client machines with a varying number of processes on

each. Note: the x-axis is logarithmic.

Figure 5: Results for the sequential and random read workloads

running on six client machines with a varying number of processes on

each. Note: the x-axis is logarithmic.

We ran the read workloads using six client machines to observe how

well rt-privacy scales. As we can see from

Figure 5, rt-privacy and

privacy behave almost identically, showing that scalability

is not affected by the stronger security.

4 Related Work

In this section we describe other cryptographic systems for remote

storage. We first discuss systems that are based on NFS or stackable

file systems. We then focus on key management, and approaches used to

reduce the load on file servers.

NFS-based systems

Several file systems have utilized NFS to add privacy to a system.

Matt Blaze's CFS [2] is a cryptographic file system that

is implemented as a user-level NFS server. An encrypted directory is

associated with an encryption key and is explicitly attached by the

user by specifying the key. Once attached, CFS creates a directory in

the mount point that acts as an unencrypted window to the user's data.

A later paper [3] explores key escrow and the use of

smart cards to store user keys. Due to its user-space implementation,

context switches and data copies hinder CFS's performance.

Additionally, CFS uses a single key to encrypt all files under an

attached directory, which reduces security.

TCFS [4] is a cryptographic file system that is

implemented as a modified kernel-mode NFS client. To encrypt data, a

user sets an encrypted attribute on files and directories within the

NFS mount point. Every user and group is associated with a different

encryption key which is protected using the Unix login password and

stored in a local file. A second scheme also supports Kerberos-based

key management. Group access to encrypted resources is limited to a

subset of the members of a given Unix group, while allowing for a

mechanism for reconstructing a group key when a member of a group is

no longer available. TCFS has several weaknesses that make it less

than ideal for deployment. First, the reliance on login passwords as

user keys is not sufficiently secure. Also, storing encryption keys

on disk in a key database further reduces security. Finally, TCFS is

available only on systems with Linux kernel 2.2.17 or earlier,

limiting its availability.

The Self-certifying File System (SFS) [14] is an

encrypt-on-the-wire system which uses NFS to achieve portability.

Users communicate with a local SFS client using NFS RPC calls. The

client communicates with a remote SFS server which talks to an NFS

server residing on the same machine.

SFS-RO [7] is based on SFS and supports encryption on the

server-side disk. However, its usage is limited to read-only data;

file modification is not supported.

Stackable file systems

Stackable encryption file systems are portable because they can stack

on top of any existing file system. These file systems can be layered

on an NFS client to write encrypted data to a remote disk. This would

encrypt file data, but NFS-related information would be leaked on the

wire because RPC procedure names arguments would not encrypted.

The main disadvantage of stackable file systems is the performance

penalty incurred by the additional level of indirection introduced and

the need to have additional buffer pages to hold the unencrypted data.

Cryptfs [22] is the first file system of this type,

and bases its keys on process session IDs and user IDs.

NCryptfs [21] enhanced Cryptfs to support multiple

concurrent authentication methods, multiple dynamically-loadable

ciphers, ad-hoc groups, challenge-response authentication and timeouts

for keys, active sessions and authorizations.

NCryptfs uses a single key to encrypt all the files in a mount point

which has to be set when the file system is mounted.

IBM's eCryptfs [9], another Cryptfs-derived file

system, provides advanced key management and policy features.

eCryptfs stores the encryption key as a part of the file or in an extended

attribute,

and an attempt to access an encrypted file will result in a callback

to a user space utility which will then prompt the user for the

password.

Key management techniques

In addition to the key management techniques discussed in the context

of the systems above, other network storage systems used various

techniques to manage their keys. Both AFS [10]

and NASD [8] use Kerberos to provide security, but

both encrypt data only on the wire, and not on the storage, which

decreases security and performance [17].

SNAD [16] expands NASD to provide on disk

encryption. However, the main contribution from SNAD is a PKI-based

key management system. The symmetric key used to encrypt the file is

encrypted with the public keys of the users who are allowed to access

the file. Users can then access the file by decrypting the symmetric

key using their private keys, and then decrypting the file.

Microsoft's Encrypting File System (EFS) [15]

is an extension to NTFS and utilizes Windows authentication methods as

well as Windows ACLs.

EFS stores keys on the disk in a lockbox that is encrypted using the

user's login password.

Another approach to manage keys is explored by the Secure File

System [11]. It creates an ACL for each file that

contains the access permissions on the file. The file system encrypts

the file key using a trusted group server's public key and stores it

as a part of the file metadata. The access request is then forwarded

to the group server which enforces the access permissions set in the

ACL.

Reducing server load

Different approaches have been used to reduce the load on the server.

SFS-RO, like rt-privacy, avoids performing any cryptographic

operations on the server to give better performance. It stores data

in the encrypted form on untrusted servers that can be modified only

by the owner.

AFS [10], a distributed file system, caches file

data in a local disk cache.

NASD [8] proposes a distributed network of storage

drives, which relieves the server from handling data transfers.

Authorized users use capabilities attained from the server to access

network-attached disks directly.

5 Conclusions

We designed a new round-trip privacy scheme for NFSv4 which was

implemented as a new RPCSEC_GSS service called rt-privacy.

This allows for stronger privacy, which is especially important when

using NFSv4 over the Internet.

We leveraged the extensibility of the established RPCSEC_GSS protocol

to seamlessly add our security service. We also utilized the

extensibility of NFSv4 to add our key management system without

modifying the protocol. Our privacy service not only provides

increases security, but also reduces the load on the server when

compared to other privacy options. In our experiments we saw that

rt-privacy often significantly improved throughput and scaled

well. We have made the source code for rt-privacy available

at www.fsl.cs.sunysb.edu/project-secnetfs.html.

Future Work

We plan to implement a more flexible key management scheme, and allow

users to specify which files should be stored in encrypted form. We

also plan to encrypt meta-data, such as file names.

In addition, we can further modify our RPCSEC_GSS service to allow

for round-trip integrity [1].

We will also look into potential performance improvements gained from

incorporating compression into rt-privacy. Data can be

compressed before being encrypted, and decompressed after being

decrypted. This can potentially improve performance in systems that

have network or disk bottlenecks, as well as saving disk space on the

server.

6 Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers and J. Bruce Fields for their

comments, the Linux NFSv4 developers for their prompt responses and

bug fixes, Radu Sion for his advice in the initial stages of

the work, and Justin Seyster for recommending CTR-mode encryption.

References

- [1]

-

A. Aggarwal.

Extensions to NFSv4 for checksums.

Technical Report Internet-Draft, Network Working Group, May 2006.

- [2]

-

M. Blaze.

A cryptographic file system for Unix.

In Proc. of the first ACM Conf. on Computer and

Communications Security, pp. 9-16, Fairfax, VA, 1993

- [3]

-

M. Blaze.

Key management in an encrypting file system.

In Proc. of the Summer USENIX Technical Conf., pp.

27-35, Boston, MA, June 1994.

- [4]

-

G. Cattaneo, L. Catuogno, A. Del Sorbo, and P. Persiano.

The design and implementation of a transparent cryptographic

filesystem for Unix.

In Proc. of the Annual USENIX Technical Conf.,

FREENIX Track, pp. 245-252, Boston, MA, June 2001.

- [5]

-

W. Diffie and M. E. Hellman.

Privacy and authentication: An introduction to cryptography.

Proc. of the IEEE, 67(3):397-427, 1979.

- [6]

-

M. Eisler, A. Chiu, and L. Ling.

RPCSEC_GSS protocol specification.

Technical Report RFC 2203, Network Working Group, September 1997.

- [7]

-

K. Fu, M. F. Kaashoek, and D. Mazi`eres.

Fast and secure distributed read-only file system.

Computer Systems, 20(1):1-24, 2002.

- [8]

-

H. Gobioff.

Security for a High Performance Commodity Storage Subsystem.

PhD thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, May 1999.

- [9]

-

M. Halcrow.

eCryptfs: a stacked cryptographic filesystem.

Linux Journal, (156):54-58, April 2007.

- [10]

-

J. H. Howard, M. L. Kazar, S. G. Menees, D. A. Nichols,

M. Satyanarayanan, R. N. Sidebotham, and M J. West.

Scale and performance in a distributed file system.

ACM Transactions on Computer Systems, 6(1):51-81, February

1988.

- [11]

-

J. P. Hughes and C. J.Feist.

Architecture of the secure file system.

In Proc. of the 18th International IEEE Symposium on Mass

Storage Systems and Technologies, pp. 277-290, San Diego, CA, April

2001

- [12]

-

N. Joukov, A. Traeger, R. Iyer, C. P. Wright, and E. Zadok.

Operating system profiling via latency analysis.

In Proc. of the 7th Symposium on Operating Systems Design

and Implementation, pp. 89-102, Seattle, WA, November 2006.

ACM SIGOPS.

- [13]

-

H. Lipmaa, P. Rogaway, and D. Wagner.

CTR-mode encryption.

In In First NIST Workshop on Modes of Operation, Baltimore,

MD, October 2000. NIST.

- [14]

-

D. Mazières, M. Kaminsky, M. F. Kaashoek, and E. Witchel.

Separating key management from file system security.

In Proc. of the 17th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems

Principles, pp. 124-139, Charleston, SC, December 1999

- [15]

-

Microsoft Research.

Encrypting file system for windows 2000.

Technical report, Microsoft Corporation, July 1999.

- [16]

-

E. Miller, W. Freeman, D. Long, and B. Reed.

Strong security for network-attached storage.

In Proc. of the First USENIX Conf. on File and

Storage Technologies, pp. 1-13, Monterey, CA, January 2002.

- [17]

-

E. Riedel, M. Kallahalla, and R. Swaminathan.

A framework for evaluating storage system security.

In Proc. of the First USENIX Conf. on File and

Storage Technologies, pp. 15-30, Monterey, CA, January 2002.

- [18]

-

RSA Laboratories.

Password-based cryptography standard.

Technical Report PKCS #5, RSA Data Security, March 1999.

- [19]

-

S. Shepler, B. Callaghan, D. Robinson, R. Thurlow, C. Beame, M. Eisler, and

D. Noveck.

NFS Version 4 Protocol.

Technical Report RFC 3530, Network Working Group, April 2003.

- [20]

-

C. P. Wright, N. Joukov, D. Kulkarni, Y. Miretskiy, and E. Zadok.

Auto-pilot: A platform for system software benchmarking.

In Proc. of the Annual USENIX Technical Conf.,

FREENIX Track, pp. 175-187, Anaheim, CA, April 2005.

- [21]

-

C. P. Wright, M. Martino, and E. Zadok.

NCryptfs: A secure and convenient cryptographic file system.

In Proc. of the Annual USENIX Technical Conf., pp.

197-210, San Antonio, TX, June 2003.

- [22]

-

E. Zadok, I. Badulescu, and A. Shender.

Cryptfs: A stackable vnode level encryption file system.

Technical Report CUCS-021-98, Computer Science Department, Columbia

University, June 1998.

- [23]

-

E. Zadok, R. Iyer, N. Joukov, G. Sivathanu, and C. P. Wright.

On incremental file system development.

ACM Transactions on Storage (TOS), 2(2):161-196, May 2006.

Footnotes:

1Appears in the proceedings of the Third ACM Workshop on

Storage Security and Survivability (StorageSS 2007). This

work was partially made possible by the NSF HECURA

CCF-0621463 award and an IBM Faculty Award.

File translated from

TEX

by

TTH,

version 3.76.

On 22 Aug 2007, 18:48.